Founding Principles of the United States: The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union is the first constitution of the United States. When the colonies of British America secured their independence from Great Britain, each colony became a free, sovereign, and independent nation, a fact that is expressly recognized by the British government in the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Americans at the time were agreed among themselves that they needed some kind of political union for common defense and to facilitate free trade among the states. In the early years of American independence, Britain, France, and Spain were active in North America, and as imperial powers, were a danger to the American states without a political arrangement among them for mutual defense. For example, the Americans did not so much defeat the British in our war for independence as Britain simply gave up the fight. At the time, the British Empire was at war with multiple nations and the shoot-out with the Americans was seen as an unnecessary distraction. There was discussion among the British when the decision was taken to let the Americans go that when things calmed down elsewhere in the Empire, they could then commit the necessary resources, should they desire, to re-imposing British rule over the former colonies. This danger was acknowledged as well as the possibility that any single state could be conquered by France or Spain, and so the need for a union for common defense was clear to all (possibly excepting Rhode Island which was reluctant in the early years to join the union).

When independent sovereign states enter into alliances, what is the nature of the agreement among them? The answer to this question is suggested in the title of the constitution agreed to among the states. The Articles of Confederation established a “perpetual” union. But the perpetual union established among the thirteen American states in 1781 ended in 1788 when nine states withdrew from it (without charges of “treason”). What, then, is a “perpetual union”? The Articles of Confederation, like the Constitution of the United States, was a compact among sovereign states. A compact (a contract) is said to be perpetual when it has within it no term of duration. If a compact does not stipulate an end date, it is said to be a compact of perpetual term, or a compact-at-will, which means that the parties to the compact may negotiate a departure from it as each party deems proper. There is no such thing in law as a compact into which people may enter at will, but once a party to the compact, may never leave on pain of force and violence. Moreover, no living generation may agree to a political compact that binds their descendants forever thereafter. It is odd indeed to say, following the Declaration of Independence, that the authority of government rests on the consent of the governed, and then insist nevertheless that future generations must abide by the current political order whether they like it or not. Every compact must provide for rescission, for the parties to it to withdraw from it, otherwise it is not a compact but an instrument of continual political control which cannot exist among a free and sovereign people. In other words, where such an instrument of political control is in force, the people living under it are not free, regardless of official rhetoric. This shows us what people in our founding generation understood well: for freedom to flourish, government must be kept to its narrow and proper functions, and thus usurpations of power must be resisted the moment they appear. The concern here is the dreaded precedent. If we allow an unlawful act by government, we have accepted that government may act outside the law that governs it, and thus there are no functioning limits on its power.

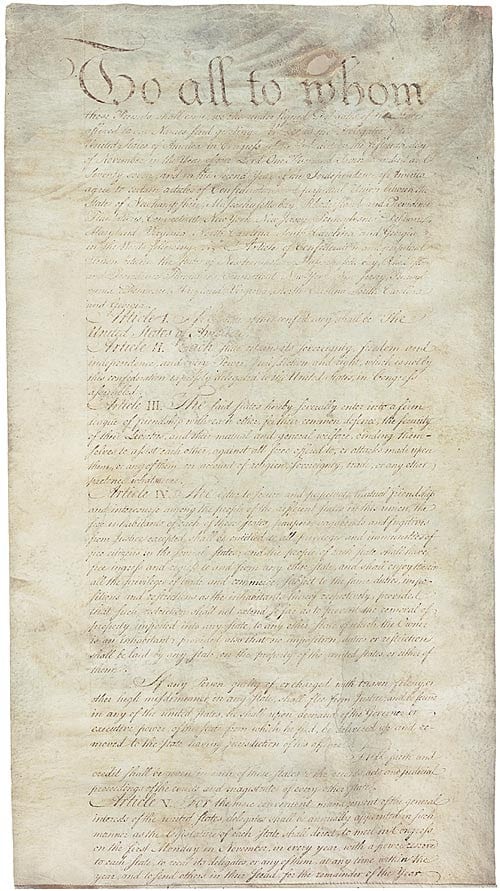

The Articles of Confederation was designed to establish a general government that was sufficiently bounded that its officers could not grow its power. The Congress had a house of delegates but no senate. There was no executive and no court (except courts for trying acts of piracy and other felonies committed on the high seas). The reason for this was simply that each state had a governor and its own courts, so a federal executive and supreme court would add nothing but opportunities for federal mischief. The Articles of Confederation were formally adopted by the states on November 15, 1777, but didn’t go into effect until 1781. The document contains thirteen articles of which we will consider the ones that express the political principles animating it.

The first Article gives us a name: “The Stile of this confederacy shall be ‘The United States of America’.” The second Article declares the new confederacy to be based on the principle of federalism that will be expressed in the tenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States. “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” So the general government has only those powers that are “expressly delegated” to it in the Articles of Confederation. Every other power, no matter what, is retained by the states individually and to the people thereof. Thus every act of the general government that is not grounded in the basic law of the Articles is a usurpation of power and not a law at all, and so the means of dealing with such a usurpation is to correct the government immediately by declaring the offending act to be “null, void, and of no force or effect.” It is foundational to a government founded on the principle of federalism that sovereign, independent states retain at all times the power to nullify unconstitutional laws of the general government.

Recall that the Articles of Confederation is a compact among sovereign nations, and so when the general government acts beyond its stipulated authority, it violates the compact and so its act has no force within the common agreement among the states. When a compact is violated, the parties to it are released from obligation to the agreement unless the parties correct the error.

Under the Articles, and under the Constitution, the method of correction is to declare the unlawful act to be null and void, and to refuse to comply with it. The general government under the Articles and the Constitution is an artificial corporation for specified and limited purposes and nothing more. It possesses no sovereignty of its own because the general government is not a party to the compact, but rather is an agent of the sovereign states that produced it.

The third Article explains the purpose of the confederation. “The said states hereby enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.”

A league is a gathering of independent persons or entities for agreed-upon purposes, and in this Article the members are clear to enumerate the purposes agreed to.

There is nothing in this Article that confers on the Congress authority to educate children, run hospitals, manage agriculture, build roads and bridges, provide for the retirement of the aged, or whatever else people in government may want to do.

All such concerns, according to the second Article, are matters for the people of each state to decide for themselves. The sovereign people of South Carolina may have different ideas about education than do the sovereign people of New York, and so the insistence on having uniform laws on such matters emanating from the center is a frightful intrusion on the sovereign freedom of a state. The reference to general welfare, also in the Constitution of the United States, is, of course, intolerably vague, but in the Articles of Confederation it remains that whatever people in government might assert “general welfare” to mean, the general government has only those powers “expressly delegated” to it. In the Articles of Confederation, there are no implied powers.

Article five provides in part for selecting and regulating delegates to the Congress. Each state shall have no fewer than two and no more than seven delegates. When Congress is in session, it is the responsibility of each state to provide material support for its delegation. Moreover, delegates are to be selected by a method to be determined by each state, and each state legislature possesses the authority to recall its delegates at any time and to replace them as deemed proper. This, of course, is intended as an absolute brake on confederal usurpations of power. If it came to a contest between Congress and the states, the states may simply recall their delegates and put an end to the business of the offending legislative body.

Perhaps what was most objectionable about the Articles of Confederation to the nationalists of the time, like Alexander Hamilton, was that the Congress had no power to tax. The revenues for operating the general government were to be raised by the state legislatures according to a formula laid out in the eighth Article. However, if a state decided to send less money than determined, and arguably even none, the general government had no recourse at its disposal. This made many men of the governing class at the time seethe with frustration. Gouverneur Morris of New York reportedly insisted that if it helped get rid of the Articles of Confederation, he would argue that under its government, water wouldn’t boil. Happily, no one in office today would ever think this way…

After a few years of government under the Articles of Confederation, there was much displeasure expressed about it. True federalists, like Thomas Jefferson, very much liked the Articles for its constraints on government, but others, including George Washington who feared the general government under the Articles was too weak to provide for the common defense, wanted to replace the document with one of “a more energetic government.” Importantly, one with power to tax. There were a few efforts to organize a convention for a new constitution, but opposition to it was too great for success. At length, James Madison and others got agreement for a convention in Philadelphia in 1787 to prepare amendments to the Articles of Confederation for the states to consider. When the delegates convened in May, their first act was to swear themselves to secrecy (James Madison died without publishing his notes on the convention). Although it was a hot summer in 1787, the delegates kept the windows closed in the room where they met so that people outside could not hear them. The delegates then proceeded to write a new constitution for the United States, one of a more energetic government. Those Americans who wanted to keep the Articles, it seems, went along with the new constitution, with amendments, because they feared the union would break apart over dislike of the Articles of Confederation among nationalists, and the loss of security within the union was thought more grievous than the dangers to liberty of the new, more energetic government. So a new constitution was written and ratified, and Americans have been coping with the stresses of interpreting it ever since.

Posted on: February 14, 2023