Front and Center Vol 2 No 1 January 2023

FRONT AND CENTER

Vol. 2, No 1, January 2023

Mission

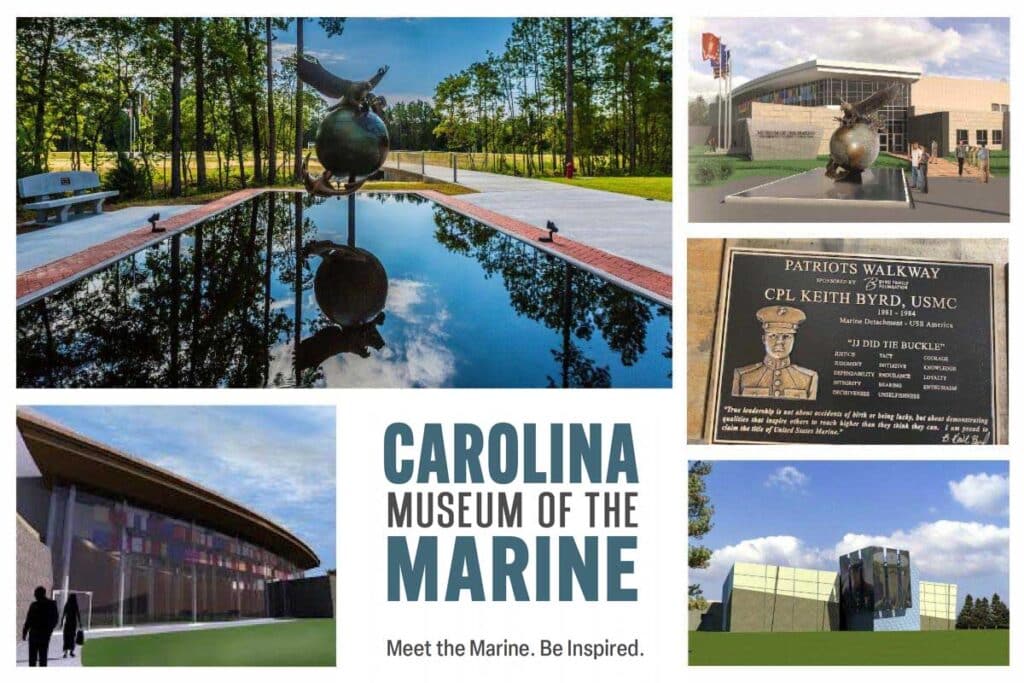

Honoring the legacy of Carolina Marines and Sailors and inspiring future generations.

A Message from the CEO

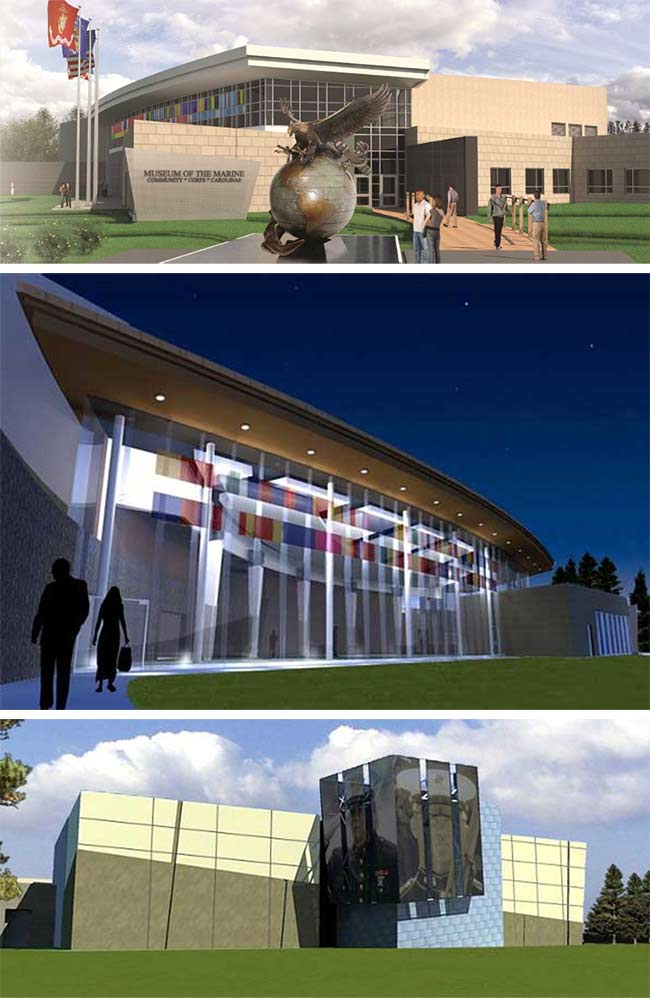

Happy New Year! 2023 is going to be an exciting year for the Carolina Museum of the Marine. We have selected Ralph Applebaum Associates (RAA) as our Exhibit Designer. RAA is one of the world’s longest established and largest museum exhibit design firms with a wealth of experience. Also, we are conducting final interviews this week for a General Contractor and will announce that selection once finalized.

As we start 2023, it is important to remind ourselves what we stand for. Our mission is straight forward and meaningful:

- Honoring the legacy of Carolina Marines and Sailors

- Sustaining the ideals that are the foundation of our nation

- Inspiring principled, committed citizens

We will serve as a lasting tribute and living legacy to the contributions of the Marines and Sailors who have served in the Carolinas since the beginning of World War II. We will honor their commitment and service to the Corps, and the communities who support them, with an extraordinarily personalized, state of the art museum emphasizing the critical role they have played in the development of technological and tactical innovations.

With your continued support, the positive momentum gained will continue throughout 2023.

Semper Fi,

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret)

Chief Executive Officer

Situation Report: The Museum

A quick update on construction planning for the Museum

Congratulations to Ralph Applebaum Associates, Exhibit Designers. We look forward to working with you to create an unforgettable museum and Al Gray Marine Leadership Forum experience!

General Contractors Finalists Selected:

1). T.A. Loving and 2) Samet Corporation

We will keep you posted as the process moves forward, but we are on track to have the “team” in place by the end of the year.

Want to stay informed about our progress?

In Their Own Words…

SgtMaj Raquel Painter, USMC (Ret) talks about…

Courage

Al Gray Marine Leadership Forum Essays

The intent of these essays is to create civil discourse and spur thought. In line with our mantra of “teaching how to think, not what to think” these essays are complex, and the issues addressed are difficult to navigate without sparking some disagreements.

We welcome this, as we work to inspire principled and committed leaders.

Founding Principles of the United States:

The Spirit of ’76

by James Danielson, PhD

USMC Veteran

With the publication of the Declaration of Independence, we may say that we come to the beginning of the United States as a union of mature political societies. Of course, we could have an interesting and probably interminable conversation about the origins of the United States if we look for what we might call the “seeds” of the people from England who first settled here. In his excellent multi-volume history of colonial America Conceived in Liberty, Murray Rothbard begins his discussion of the origins of America with long-ago migrations of northern Europeans into the British Islands. Yet with the Declaration of Independence, the thirteen colonies of British America became thirteen free, sovereign, and independent states, assuming “among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.” At this point, we can say that the new states had become mature political societies able fully to govern themselves without the assistance of outsiders. The political principles that animated Americans of our founding generation are written into the Declaration of Independence, and were held to embody the Spirit of ’76. In what follows we will examine this spirit, and it should be born in mind that the form of government established under its principles is rather different in its self-understanding than many Americans today will find familiar. Yet this is an important part of American history, and thus it is important to understand it.

The independence of the thirteen American states was formally recognized by the British crown in the Treaty of Paris in 1783. That treaty says in Article I: “His Britannic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and independent States; and he treats with them as such, and for himself his Heirs & Successors, relinquish all claims to the Government, Propriety, and Territorial Rights of the same and every Part thereof.” In this article of the treaty, we find the word “sovereign.” This word appears for the first time in the development of western political thought in 1576 in Six Books of the Republic by Frenchman Jean Bodin. We may say in brief scope that sovereignty is the authority to govern without the permission of another. But where does sovereignty lie? Who has it? Is it something to which some people have a right and others do not, such that some people have the authority to command and others the obligation to obey? Can sovereignty be divided? These questions animated the people of our founding generation, as it did English legal thinkers, because it was to them a foreign notion of limited value, sitting uneasily with the idea that the English political tradition is an organic growth, and not a product of rational design. However, the idea of sovereignty developed with the rise of the national state as a form of government in the sixteenth into the seventeenth centuries, and in this development, sovereignty was the defining property of governments. It was embraced by the British crown, and later by the Parliament, but in America, the idea developed a very different expression.

The idea of the state as it developed, rather violently, in Europe is that the state is an agency of coercive authority having a monopoly in the use of force over a prescribed territory, the right to command the people living in that territory, and the right also to extract its revenues from those people. When we consider this definition of the state, it becomes clear that the state is not compatible with liberty as Americans understood it since the state claims authority to command people’s conduct without their consent, and to take such portions of people’s property as they deem necessary. The great Virginia patriot Richard Henry Lee famously pointed out that “[i]f Parliament may take from me one shilling in the pound, what security have I left for the other nineteen?” The idea being asserted is that if some person or institution in society may take property (which money is) from me without my consent, I cannot be said to be free. This emphasis on the freedom of the individual, understood as a requirement of the rights we each hold by nature, leads to a different form of government than had developed in Europe.

In 1765, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act that imposed a tax on paper products in the colonies. So if one owned books, newspapers, pamphlets, letters, even playing cards, they had to bear the King’s stamp showing the owner had paid the tax. It is usual to say that Americans opposed “taxation without representation,” but this phrase is too ambiguous to communicate much of value since it entails the idea that if a duly elected representative legislature decided to tax voters at a rate of 100%, that would be fine. The quote above from Richard Henry Lee is an expression of the commonly held view that any tax on incomes, that is, any direct tax on citizens, is oppressive by its nature and not to be tolerated.

In 1774, Thomas Jefferson wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America. A reader can see in this document the approach of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson is clear to say to the British king that Americans are no longer asking for their rights to be respected, but are now demanding it. Toward the end of the document, when Jefferson is making the American position clear to the king, he writes: “Let those flatter, who fear: it is not an American art. To give praise where it is not due, might be well from the venal, but would ill beseem those who are asserting the rights of human nature. They know, and will therefore say, that kings are the servants, not the proprietors of the people.” This last sentence insisting that kings are the servants of the people and not their proprietors reverses the British understanding of sovereignty in which the people are not properly called citizens, but subjects of the sovereign crown. An important element of the American Spirit of ’76, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, is that each state is a sovereign political society with the right and authority to govern held by the people thereof.

In the Declaration of Independence, we read that it is to protect our rights to life, liberty, and property (which is the meaning of “happiness”) that people establish governments among themselves, and thus if government fails in its narrow purpose, “”it is the right of the People to alter or abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” It is important to note here that this assertion of the right of the people both to establish government and to abolish it when it misbehaves is exactly how true sovereignty of the people works. Kings are the servants, not the proprietors, of the people. This principle of local sovereignty of the people is re-enforced a bit farther into the Declaration thus: “But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism [‘in all cases whatsoever’], it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security” (emphasis added). We should observe here that by the mid-19th century, leaders in the North in general and particularly in New England, had come to call this sort of thing, that is, people choosing to throw off a despotic government, “treason.” Contemporary Americans should discuss this question of treason since it is a serious charge that has been used frequently, and a good place for this conversation to begin is Article III, section 3 of the Constitution where treason against the United States is defined.

The Spirit of ’76 is the spirit of independence and the liberty of individuals in their communities, where alone self-government can be exercised. If the people are sovereign, then government is a creature of the people and thus subject to them. This supervision of government was done throughout the colonial period through conventions of the people in their various colonies. The Philadelphia Convention of 1787 that produced our Constitution was a convention of the states in which the states chose delegates to represent them, and to return the product of their deliberations to the states for debate and ratification in conventions of the people in each state. Moreover, if the people are sovereign, then government is not sovereign, for in the theory of sovereignty, it cannot be divided, for then one half of the division could not govern without the permission of the other half, which is not sovereignty. Having set down a list of the “long train of abuses and usurpations” of the British crown, the Declaration of Independence ends in a way that is fitting for free, sovereign people.

“We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. –And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Desert Storm

by CWO5 Lisa Potts USMC (Ret)

On December 10, 1990, more than 24,000 Marines of the II Marine Expeditionary Force mustered on the parade ground at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in the largest formation of United States Marines in modern history.[1] The Marines deployed to Southwest Asia to support Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm as diplomatic pressure to persuade Iraqi forces to withdrawal from Kuwait waned. By the month’s end, the Carolina Marine Corps bases and stations had become ghost towns. Families, friends, and citizens across the nation anxiously followed the nonstop CNN coverage.

A decade of planning and innovation in logistics enabled the Marines and Seabees to marry up with the Maritime Prepositioned Force (MPF) at the port of Jubail, Saudi Arabia. Within 30-days, combat service support area Al Kibrit was built.[2] It included a 470-bed hospital with 9 operating rooms, a million stocked meals and 15,800 tons of ammunition, and the ability to produce over 80,000 gallons of water a day.[3] With Al Kibrit complete, mobile combat service support teams were prepared to support a fast-moving assault force of over forty thousand Marines into Kuwait against the fourth largest army in the world.

The arrival of additional breaching assets cleared the way for a second breach through the enemy minefields. The simultaneous assault of two divisions abreast avoided the complex maneuver of assault forces passing through each other’s lines. But moving the powerful 2d Marine Division to the northwest required establishing a second combat service support area twice as far from the MPF port and with less than half the time it took to build Al Kibrit.

National Archives ID: 6474248 Series Desert Storm Country: Saudi Arabia Camera Operator SSgt M.D. Masters, February 1, 1991.

“The dynamic two-division assault into Kuwait… was made possible by the ability to create a massive forward logistic support base in the middle of the desert immediately before the beginning of the ground offensive.”[1] In just fourteen days, engineers and logisticians completed Al Khanjar on a barren gravel plain, along with a new desert highway and an expeditionary airfield, Lonesome Dove, just a few miles west. Al Khanjar was immense; it covered 11,280 acres. It had over 24 miles of blast-wall berms,” the third largest Naval hospital in the world, the largest ammunition supply point in Marine Corps history covering 780 acres, and the largest fuel farm in Marine Corps history containing approximately five million gallons of fuel.[1] When the assault force arrived, Al Khanjar was ready and stocked with enough beans, bandages and bullets to sustain the force for fifteen days. Once demurred as “the tail that wags the dog,” Marine combat logistics proved a powerful element of the Marine air-ground team to deliver a 100-hour rout of Iraqi forces and the liberation of Kuwait.[2]

[1] Chronologies of the Marine Corps (Persian Gulf 1990-1991), Marine Corps History Division, Marine Corps University (usmcu.edu)

[2] O’Donovan, John A. “Combat Service Support during Desert Shield and Desert Storm: From Kibrit to Kuwait,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1991, 26.

[3] Ibid., 29.

[4] United States Marine Corps, MCDP-4 Logistics, Washington DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2018: 1-16.

[5] Charles C. Krulak, “CSS in the Desert,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1991, 25.

[6] Otto Kreisher, “Marines Desert Victory,” Naval History Magazine, February 2016, Vol. 30, no. 1.

Marines Making News…

Visit Marines.mil for up-to-date information about United States Marines who are making news

Please join us in supporting the mission of

Carolina Museum of the Marine

When you give to our annual campaign, you help to ensure that operations continue during construction and when the doors open!

Stand with us

as we stand up the Museum!

Copyright January 2022

Carolina Museum of the Marine

2022-2023 Board of Directors

Executive Committee

LtGen Gary S. McKissock, USMC (Ret) – Chair

Col Bob Love, USMC (Ret) – Vice Chair

CAPT Pat Alford, USN (Ret) – Treasurer

Col Joe Atkins, USAF (Ret) – Secretary

Mr. Mark Cramer, JD – Immediate Past Chair

General Al Gray, USMC (Ret), 29th Commandant – At-Large Member

LtGen Mark Faulkner, USMC (Ret) – At-Large Member

Col Grant Sparks, USMC (Ret) – At Large Member

Members

Mr. Tom DeSanctis

MGySgt Osceola Elliss, USMC (Ret)

Col Chuck Geiger, USMC (Ret)

Col Bruce Gombar, USMC (Ret)

LtCol Lynn “Kim” Kimball, USMC (Ret)

CWO4 Richard McIntosh, USMC (Ret)

CWO5 Lisa Potts, USMC (Ret)

Col John B. Sollis, USMC (Ret)

GySgt Forest Spencer, USMC (Ret)

Staff

BGen Kevin Stewart, USMC (Ret), Chief Executive Officer

Ashley Danielson, VP of Development

SgtMaj Joe Houle, USMC (Ret), Operations and Artifacts Director

Richard Koeckert, Accounting Manager

Carolina Museum of the Marine is a nonprofit organization that is rigorously nonpartisan, independent and objective.